By Susan Hoppert-Flämig and Natalia Cervantes

Susan Hopper-Flaemig

Natalia Cervantes

Having collected all the data for your research, it is time to return to the desk and write. For many PhD researchers, this stage is a challenging time. By then you have already climbed half of the mountain – you have read abundant literature on your topic, you have developed a good research proposal, narrowed down the research questions and gathered enough material to know the answers to your questions are somewhere in there. All of a sudden, finishing the PhD seems like a doable thing.

But the way to the top of the mountain is still long, very rocky and full of obstacles. Making sense of the data without losing your key arguments may be difficult, the writing may take much longer than expected and knowing you are the only person who can complete this particular piece of work may seem daunting.

In a way, writing up a doctoral thesis is a unique experience – the circumstances vary for each PhD researcher, the problems that appear with regard to the topic or the structure of the thesis may be quite specific, and everybody deals with problems differently. Yet, it seems that some experiences are quite common among researchers.

We have asked our Researching Security fellows about their experiences and reflected on our own experiences and would like to share these. We hope this makes the journey a bit smoother for those of you who are at the beginning or well into the writing up stage.

For most of us, writing up the thesis was quite hard and painful but there were also enjoyable moments. Verena said it was exciting in the beginning because she finally had time to process everything she had learned and observed during the field research. But having a first full draft, editing and refining the arguments was still a lot of work and probably the hardest part. In theory, writing up sounds idyllic: sitting down with a coffee and start writing seems fantastic. Both Natalia and Susan struggled getting the thoughts in their head down on paper. Susan was surprised to see how much of the intellectual process of articulating an argument actually happens during the writing. We all agreed that time management is important, and Jorrit mentioned he was relatively ‘lucky’ that his job contract had run out just before he started the writing process, which was probably the only reason that he could actually finish the PhD.

For most of us, writing up the thesis was quite hard and painful but there were also enjoyable moments. Verena said it was exciting in the beginning because she finally had time to process everything she had learned and observed during the field research. But having a first full draft, editing and refining the arguments was still a lot of work and probably the hardest part. In theory, writing up sounds idyllic: sitting down with a coffee and start writing seems fantastic. Both Natalia and Susan struggled getting the thoughts in their head down on paper. Susan was surprised to see how much of the intellectual process of articulating an argument actually happens during the writing. We all agreed that time management is important, and Jorrit mentioned he was relatively ‘lucky’ that his job contract had run out just before he started the writing process, which was probably the only reason that he could actually finish the PhD.

Talking about the difficulties of writing up, Jenna emphasised how important it is to develop your own argument and point of view: ‘It is this part where you really have to stand on your own two feet and lay out your stall. Nobody ever really prepares you for this part (or any part) and so it is incredibly daunting at the beginning. Also remembering what it is you were trying to say in the first place gets really hard after 70,000 words!’ The sheer length of the thesis was a challenge for most of us. ‘In the UK, a PhD thesis is up to 100,000 words. What they do not tell you is that you write around 300’-500,000 to get there because of the constant redrafting and editing’, Verena said. Natalia added that the PhD is as much what you write as what you delete.

For Jorrit, two problems stood out. First, finding a writing routine and keeping up that routine for a long time mattered. And while he thought the field interviews as such were interesting, going back to the recordings several times and working with them required some discipline, not least due to the background noise and the used slang. Susan missed talking to her PhD colleagues in Bradford as she did most of the writing up at home in Leipzig.

We all developed our strategies that helped us survive this period, which can be summarised in the following points:

Routine

An important commonality we found is that having daily routin es helped the process. Jorrit mentioned that having a schedule and appropriating a writing routine can make a huge difference: You will be aware of the hours of the day when you can focus better and seize them. Knowing when to step away from your thesis and take a break to clear your mind is essential. Ours involved exercising, meeting with friends and generally having time off, where you try to avoid thinking about your thesis.

es helped the process. Jorrit mentioned that having a schedule and appropriating a writing routine can make a huge difference: You will be aware of the hours of the day when you can focus better and seize them. Knowing when to step away from your thesis and take a break to clear your mind is essential. Ours involved exercising, meeting with friends and generally having time off, where you try to avoid thinking about your thesis.

In addition, having concise and attainable daily or weekly goals aids in keeping you motivated, Jorrit said. This can be in the form of little things like, revising your references, working through your formats, or writing an ‘X’ amount of words, editing sections, etc. The idea is to keep track of what you want to accomplish every day, week or month. This way you know where you stand and can take small steps before tackling bigger issues of your document.

Structure your thesis and strip it down

Ideally, your supervisor gives you some guidance regarding the structure of your thesis. But here are some general ideas (that may be so evident that you probably already know them): Thinking through the chapters and what each chapter should be doing might help make writing and editing flow easier. The headings and subheadings should help you ‘tell the story’ or convey your argument to the reader. Try to think each chapter’s heading and subheading in terms of what is the key idea it should carry.

We also found that taking a step back and going back to the beginning allows you to find again your perspective. What does the literature say, compared to the data that you gathered? What is the ‘gap’ you are looking at? A good exercise for this is trying to think about your argument and put it in 30 words or less. This will help you think through your key concepts. Nonetheless, maintaining a good relationship with your supervisor is essential even now that you are the expert of your topic. Ideally, she/ he can provide you with valuable feedback on your writing and help you when you are stuck.

Talk it out

Undeniably, talking our thesis out helped us all. For example, Jenna resorted to online forums and twitter chats, as well as reading blogs on academic writing, and seeking support in the form of writing sessions and online monthly writing challenges. She also mentioned that presenting at conferences using her data and chapter material made a difference, since getting feedback and getting used to talking about your research really helped thinking about what you are trying to do and say with it.

Similarly, Verena said that for her staying in touch with other PhD students and knowing that you are not alone and all face similar difficulties made a difference.

We sincerely hope that sharing both our challenges and how we tried to tackle them is useful to you. We have all been through dark moments whilst writing, don’t despair! Even if it seems a long way, the thesis will be done eventually, and what you learn on the way will no doubt equip you with all you need for a succesful career afterwards.

Using ArcGIS software, maps have been created for each category of insecurity (see image above). These maps were then layered to give a graphic overview of where insecurities tend to cluster geographically. With the number of incidents ranging from one to 678 events per municipality, the standard deviation distribution of data (insecurities) was used and mapped to allow identifying regions with particularly high incidents of violence. Through this process, the Magdalena Medio and Catatumbo regions were identified. Thereafter, qualitative research captured the articulations of in/security as expressed by the local communities in the selected research sites. Secondly, GIS was used to visualise the geographical priority regions of national security policy and practice. Qualitative research thereafter interrogated the implications of such policy and practice in the selected research sites. Finally, GIS was used to illustrate the geographic overlap between security related policies, peace-building initiatives and economic development priorities. These illustrations helped inform analysis of the contradictions between state-level security understandings and practice, and how communities experience in/security at the local level.

Using ArcGIS software, maps have been created for each category of insecurity (see image above). These maps were then layered to give a graphic overview of where insecurities tend to cluster geographically. With the number of incidents ranging from one to 678 events per municipality, the standard deviation distribution of data (insecurities) was used and mapped to allow identifying regions with particularly high incidents of violence. Through this process, the Magdalena Medio and Catatumbo regions were identified. Thereafter, qualitative research captured the articulations of in/security as expressed by the local communities in the selected research sites. Secondly, GIS was used to visualise the geographical priority regions of national security policy and practice. Qualitative research thereafter interrogated the implications of such policy and practice in the selected research sites. Finally, GIS was used to illustrate the geographic overlap between security related policies, peace-building initiatives and economic development priorities. These illustrations helped inform analysis of the contradictions between state-level security understandings and practice, and how communities experience in/security at the local level. The year 2017 started with the news of a series of massacres in prisons across Brazil triggered by power struggles between the country’s two most notorious drug gangs – the Comando Vermelho and the Primeiro Comando da Capital. As these tragic events brought the problem of gang violence once again to international attention, the question of how to best to respond to the challenge posed by criminal gangs has become as relevant as ever. In this post, I will argue for a shift beyond common responses such as coercive mano dura policies and cooperative gang truces towards an integrated approach of substitutive security governance aimed at replacing the functions gangs fulfil for their different stakeholders.

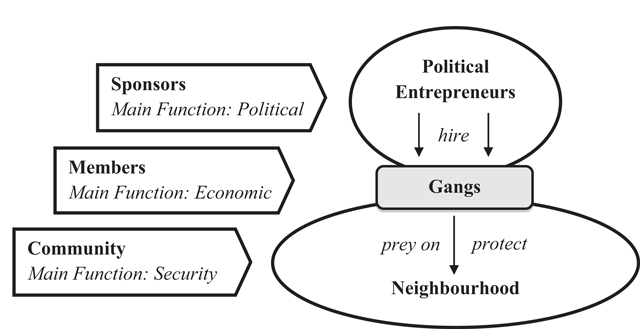

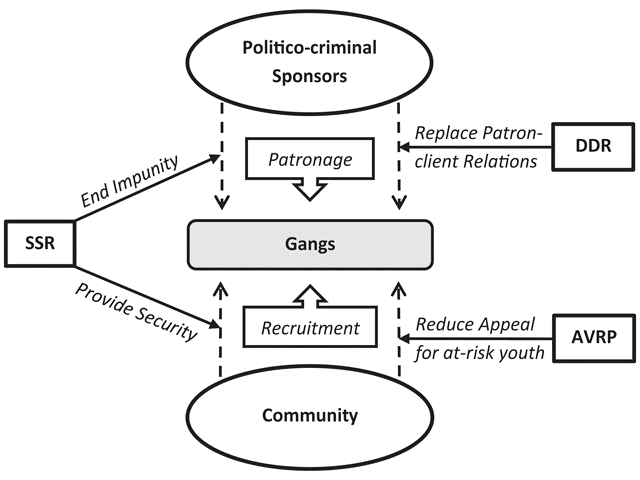

The year 2017 started with the news of a series of massacres in prisons across Brazil triggered by power struggles between the country’s two most notorious drug gangs – the Comando Vermelho and the Primeiro Comando da Capital. As these tragic events brought the problem of gang violence once again to international attention, the question of how to best to respond to the challenge posed by criminal gangs has become as relevant as ever. In this post, I will argue for a shift beyond common responses such as coercive mano dura policies and cooperative gang truces towards an integrated approach of substitutive security governance aimed at replacing the functions gangs fulfil for their different stakeholders.

For most of us, writing up the thesis was quite hard and painful but there were also enjoyable moments.

For most of us, writing up the thesis was quite hard and painful but there were also enjoyable moments.  es helped the process. Jorrit mentioned that having a schedule and appropriating a writing routine can make a huge difference: You will be aware of the hours of the day when you can focus better and seize them. Knowing when to step away from your thesis and take a break to clear your mind is essential. Ours involved exercising, meeting with friends and generally having time off, where you try to avoid thinking about your thesis.

es helped the process. Jorrit mentioned that having a schedule and appropriating a writing routine can make a huge difference: You will be aware of the hours of the day when you can focus better and seize them. Knowing when to step away from your thesis and take a break to clear your mind is essential. Ours involved exercising, meeting with friends and generally having time off, where you try to avoid thinking about your thesis.

“Discontinuities and Resistance in Latin America”

“Discontinuities and Resistance in Latin America” ‘Peacebuilding during an age of crisis’

‘Peacebuilding during an age of crisis’ Looking at the position this individual holds, things start to get more complicated. A first common element is that the position is normally temporal, although the duration seems to vary a lot (1-5 years). In any case, it is often considered as a first or intermediary career step for, often young, academics, or ‘early-career researchers’ who would like to continue working at universities later in more stable positions. From the universities’ point of view, the post-doc trajectory is often considered to prepare someone for a career in academia.

Looking at the position this individual holds, things start to get more complicated. A first common element is that the position is normally temporal, although the duration seems to vary a lot (1-5 years). In any case, it is often considered as a first or intermediary career step for, often young, academics, or ‘early-career researchers’ who would like to continue working at universities later in more stable positions. From the universities’ point of view, the post-doc trajectory is often considered to prepare someone for a career in academia. Can the post-doc be more than that? Yes, especially when it comes to teaching opportunities. While many post-doc positions have no or few teaching obligations, others are fully designed to gain teaching experience. In general, there seems to be a trend towards more integration of teaching within post-doc trajectories, but again this differs between countries and between universities.

Can the post-doc be more than that? Yes, especially when it comes to teaching opportunities. While many post-doc positions have no or few teaching obligations, others are fully designed to gain teaching experience. In general, there seems to be a trend towards more integration of teaching within post-doc trajectories, but again this differs between countries and between universities.